Population growth, fuelled by immigration, is once again at the center of political debate in Switzerland. Some see it as a source of prosperity, enabling the economy to obtain the labor it needs, while others see it as a source of congestion. But the link between population growth and macroeconomic performance is in fact quite tenuous: while Switzerland has seen a sharp rise in its population since 2007, the growth in GDP per capita has not differed significantly from that of other European countries.

Sources of Swiss growth

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Swiss GDP (blue line) since 1995, with the vertical line indicating the entry into force of free labor movement in 2007. The green and red lines show changes in population and GDP per capita, the latter being an (admittedly imperfect) indicator of well-being in Switzerland. Careful observation shows that growth in GDP per capita has slowed since 2007. Is this an effect of free movement? To analyze this question, we break down the various underlying factors and compare Switzerland with other countries.

GDP per capita can be broken down into different variables that capture various aspects, such as demographics and productivity. More specifically, GDP per capita increases if 1) the working-age population increases relative to the total population, 2) the employment rate among the working-age population increases, 3) the number of hours worked per employee increases, and 4) productivity (GDP per hour) increases:

GDP / Pppulation

= Population 15-65 years / Population

x Employment / Population 15-65 years (employment rate)

x Hours worked per employed person

x GDP / Hours

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the four sources of growth. Demographics are not contributing, as the ageing of the population is causing the ratio of the working-age population to the total population to fall, an aspect that has become more marked since 2007 (grey line). Similarly, the steady trend towards shorter average working hours per employed person is reducing growth (yellow line). The last two factors have underpinned the rise in GDP per capita, with an increase in the employment rate (green line), which has accelerated since 2007, and the rise in productivity (blue line), which has, however, slowed somewhat since 2007.

Switzerland in international perspective

While the evolution of the various factors provides us with information about the situation in Switzerland, as well as any changes in trends in 2007, we cannot on this basis alone attribute the changes to free labor mobility. Other major developments occurred at that time, in particular the global financial crisis, followed by that of the Eurozone, which led to a deep recession in several countries. It is therefore necessary to compare Switzerland with other countries that were affected by the global crisis but did not implement freedom of movement. If the changes since 2007 are due to free labor mobility, then Switzerland's performance should be markedly different from that of other countries.

We compare Switzerland with other small countries in Europe (Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway) as well as with the major countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States). The analysis is based on data from the IMF (GDP, employment, population) and the OECD (GDP per hour, ratio of population aged 15-65 to total population). This post extends the analysis carried out in this blog three years ago, and a broad analysis of the theme can also be found in the April blogs by Patrick Leisibach of Avenir Suisse.

To begin with, we put population trends into perspective. Figure 3 shows the difference between the average annual growth rate from 1995 to 2007 and the average rate from 2007 to 2022 (red bars). We also show growth up to 2019 (blue bars) to avoid any distortion due to the Covid crisis. Unsurprisingly, Switzerland has seen its population growth accelerate by around half a percentage point per year since 2007. Apart from Norway and Sweden, whose situation is similar to ours, the other European countries have seen less acceleration, or even a deceleration, particularly in Spain.

We now carry out the same analysis for GDP per capita (Figure 4) and its various sources. We see that the rate of growth in GDP per capita slowed markedly from 2007, by around 1 percentage point per year. But all the other countries have experienced this trend. In fact, Switzerland is one of the countries (along with Denmark and Germany) where the decline is least marked. It would therefore be wrong to attribute the slowdown in per capita GDP growth in Switzerland to free labor mobility. It is interesting to note that the other two countries that experienced an acceleration in population growth (Sweden and Norway) experienced a particularly marked slowdown in GDP per capita. If one were to seen as a cost of high population growth, then one should recognize that Switzerland has managed the rise in its population particularly well, preventing a marked impact on GDP per capita.

We decompose the growth rates in GDP per capita shown in Figure 4 into the growth rates of the four underlying factors. The ageing of the population has led to a decline in the working-age population relative to the total population, which has been more marked since 2007 (Figure 5). It should first be noted that this factor does not play a major role, as the values on the horizontal scale show. Switzerland is on a par with the other small countries, where this aspect is less pronounced than among the large countries. While the positive values for Germany and Italy may come as a surprise, it should be remembered that the graph does not show the growth rate of the population aged 15-65 in relation to the total population, but rather the change in this growth rate between 1995-2007 and since then. As these two countries have been facing the challenge of ageing for longer than the others, this challenge has not become more acute for them.

Figure 6 shows changes in the employment rate (employment as a proportion of the working-age population). This factor has deteriorated in most countries, notably Spain, contributing to the slowdown in per capita GDP growth. Switzerland, along with Germany and Sweden, is the exception, as the smooth functioning of the Swiss labor market enabled the employment rate to grow faster after 2007 than before. So free labor mobility has clearly not been to the detriment of employment.

The reduction in the number of hours per person employed has accelerated in Switzerland since 2007, slowing growth in GDP per capita (Figure 7). By international comparison, Switzerland is about average. A number of other countries have seen a sharper decline, while others, such as the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway, have seen an increase in the number of hours worked. It should be noted, however, that the decline in working hours makes only a small contribution to the slowdown in GDP per capita, as shown by the values on the horizontal scale in the figure.

The final factor is productivity, i.e. growth in GDP per hour worked, illustrated in Figure 8. We see a clear slowdown in the rate of productivity growth since 2007. By international comparison, Switzerland is doing rather well: few countries have seen a smaller reduction, and many have seen this growth slow more sharply. Consequently, we cannot conclude that free labor mobility has led Swiss companies to rest and relax their efforts to improve productivity. If, on the basis of the Swedish and Norwegian cases, we nonetheless wanted to draw such a conclusion, we would have to admit that there too Switzerland has managed to do very well.

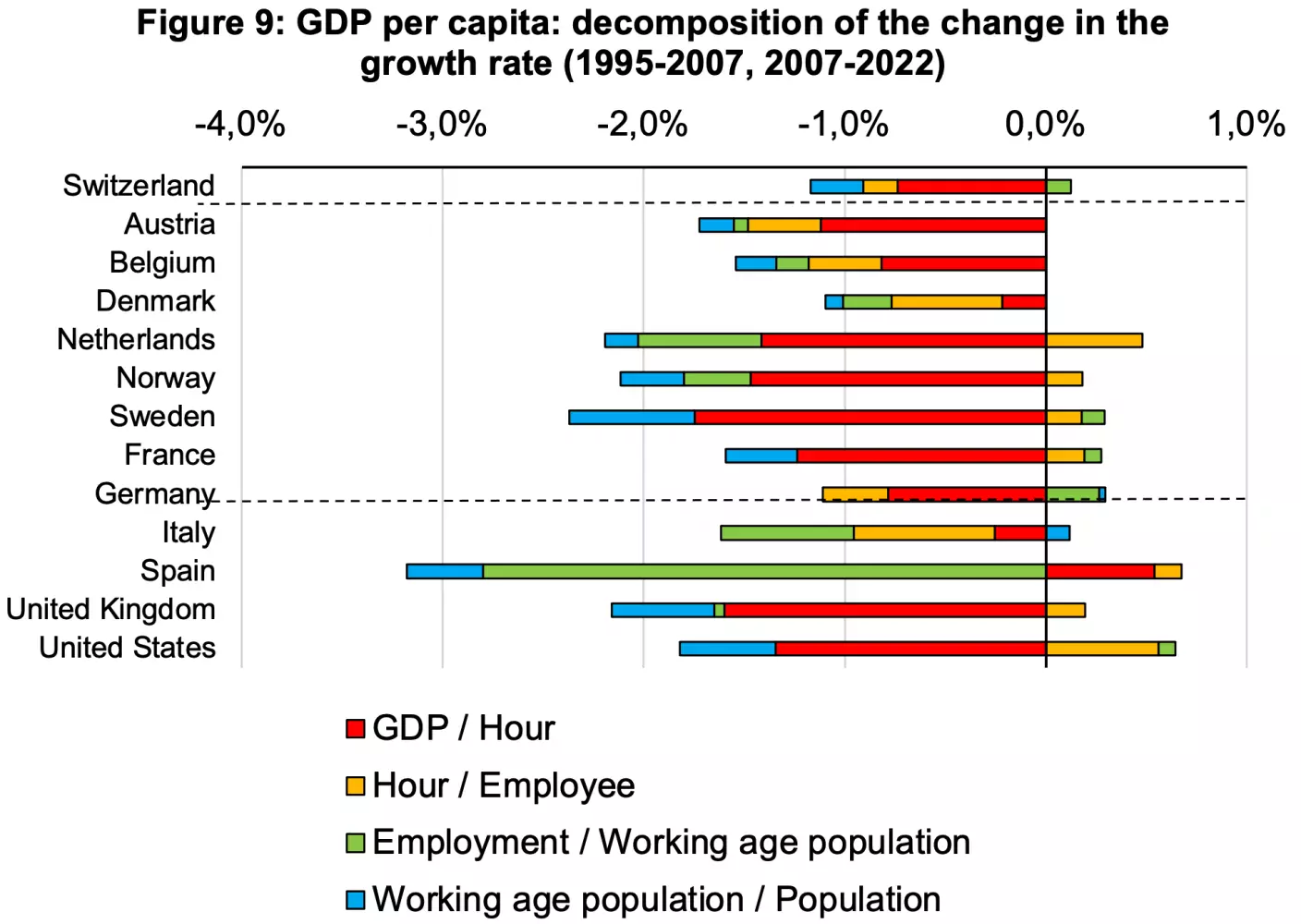

By way of summary, Figure 9 shows the contribution of the four factors to the slowdown in GDP per capita growth (Figure 4, focusing on the periods 1995-2007 and 2007-2022). The most important factor is the slowdown in productivity (red bars, corresponding to Figure 8). By international comparison, Switzerland has experienced a limited slowdown in productivity, and has managed to increase its employment rate (green bar, corresponding to Figure 6).

Changes in labor productivity (Figure 8) reflect two aspects, namely the capital intensity of production (investment increases capital productivity) and so-called multifactor productivity, which indicates the increase in production due to innovation (at constant capital and labor). Figure 10 shows the change in the growth rate of this productivity, based on OECD data. The pattern is similar to that shown in Figure 8, i.e. the slowdown has been less marked in Switzerland than in most other countries.

Is there a relationship with population growth?

To illustrate a possible link between population growth and the various factors discussed above, Figure 11 contrasts the change in the population growth rate (horizontal axis corresponding to Figure 3) with the change in the GDP per capita growth rate (vertical axis corresponding to Figure 4). The figure shows that there is no correlation between the two variables, whether we take the Covid period into account or not. An econometric analysis confirms this impression, showing that the correlation between GDP per capita growth and population growth is not significantly different from zero.

Figure 12 presents a similar analysis, considering productivity (GDP per hour) rather than GDP per capita. We find an inverse relationship between the variables, with the countries that experienced the largest acceleration in population growth being those where productivity slowed most sharply (econometric analysis shows that the link is statistically significant). However, this relationship reflects the particular situation of Spain. The relationship between the two variables disappears if we exclude this country from the sample.

In fact, Switzerland's performance is quite favorable by international comparison.

Cédric Tille

In the end, it appears that population growth is not correlated with the other variables, and that its only impact is to increase GDP growth. But even this effect is debatable. Figure 13 shows the relationship between population growth and GDP growth. While it shows a positive and statistically significant relationship, this result disappears if Spain is not taken into account. The analysis of the evolution of GDP per capita and its components shows no link with population growth. Admittedly, Switzerland experienced a clear slowdown in GDP per capita and productivity in 2007, the year in which free movement came into effect. But this must be seen as a coincidence, as 2007 also marked the start of the prolonged crisis that has weighed on growth in all industrialized countries. In fact, Switzerland's performance is quite favorable by international comparison.

Free labor mobility does not appear to have had any major impact on GDP per capita or productivity: it has not worsened them (their trend since 2007 is not significantly worse in Switzerland than elsewhere), but neither has it stimulated them (the trend is not significantly better). Admittedly, this finding is based on macroeconomic variables at country level, and it is possible that analyses focusing on certain sectors or regions might give a different picture. The fact remains that there is no obvious impact of population growth. Instead, the economic policy debate should focus on ways of improving the functioning of the labor market (for example, through the availability of crèches, or the employment of relatively old people) and increasing productivity (for example, by limiting the dominant positions of oligopolies).